Farewell to the International Brigades in Barcelona, Spain

It is hard to say a few words in farewell to the heroes of the International Brigades, both because of what they are and what they represent.

A feeling of sorrow, an infinite grief catches our throats … sorrow for those who are going away, for the soldiers of the highest ideal of human redemption, exiles from their countries, persecuted by the tyrants of all peoples… grief for those who will stay here forever, mingling with the Spanish soil or in the very depths of our hearts, bathed in the light of our gratitude.

You came to us from all peoples, from all races. You came like brothers of ours, like sons of undying Spain; and in the hardest days of the war, when the capital of the Spanish Republic was threatened, it was you, gallant comrades of the International Brigades, who helped to save the city with your fighting enthusiasm, your heroism and your spirit of sacrifice.

For the first time in the history of the peoples’ struggles, there have been the spectacle, breath-taking in its grandeur, of the formation of International Brigades to help save a threatened country’s freedom and independence, the freedom and independence of our Spanish land.

They gave us everything: their youth and their maturity; their science or their experience; their blood and their lives; their hopes and aspirations — and they asked us for nothing at all. That is to say, they did want a post in the struggle, they did aspire to the honor of dying for us.

Mothers! Women! When the years pass by and the wounds of the war are being stanched; when the cloudy memory of the sorrowful, bloody days return in a present of freedom, peace and well-being; when the feelings of rancor are dying away and when pride in a free country is felt equally by all Spaniards, then speak to your children. Tell them of these men of the International Brigades.

Tell them how, coming over seas and mountains, crossing frontiers bristling with bayonets, watched for by raving dogs thirsting to tear at their flesh, these men reached our country as crusaders for freedom, to fight and die for Spain’s liberty and independence which were threatened by German and Italian fascism.

Today they are going away. Many of them, thousands of them, are staying here with the Spanish earth for their shroud, and all Spaniards remember them with the deepest feeling.

Comrades of the International Brigades: political reasons, reasons of state, the welfare of that same cause for which you offered your blood with boundless generosity, are sending you back, some of you to your own countries and others to forced exile. You can go proudly. You are history. You are legend. You are the heroic example of democracy’s solidarity and universality.

We shall not forget you, and when the olive tree of peace puts forth its leaves again, entwined with the laurels of the Spanish Republic’s victory — come back!

Come back to us. With us those of you have no country will find one, those of you who have to live deprived of friendship will find friends, and all of you will find the love and gratitude of the whole Spanish people who, now and in the future, will cry out with all their hearts:

“Long live the heroes of the International Brigades!”

Address by Her Excellency, the Right Honourable Adrienne Clarkson, the Governor General of Canada

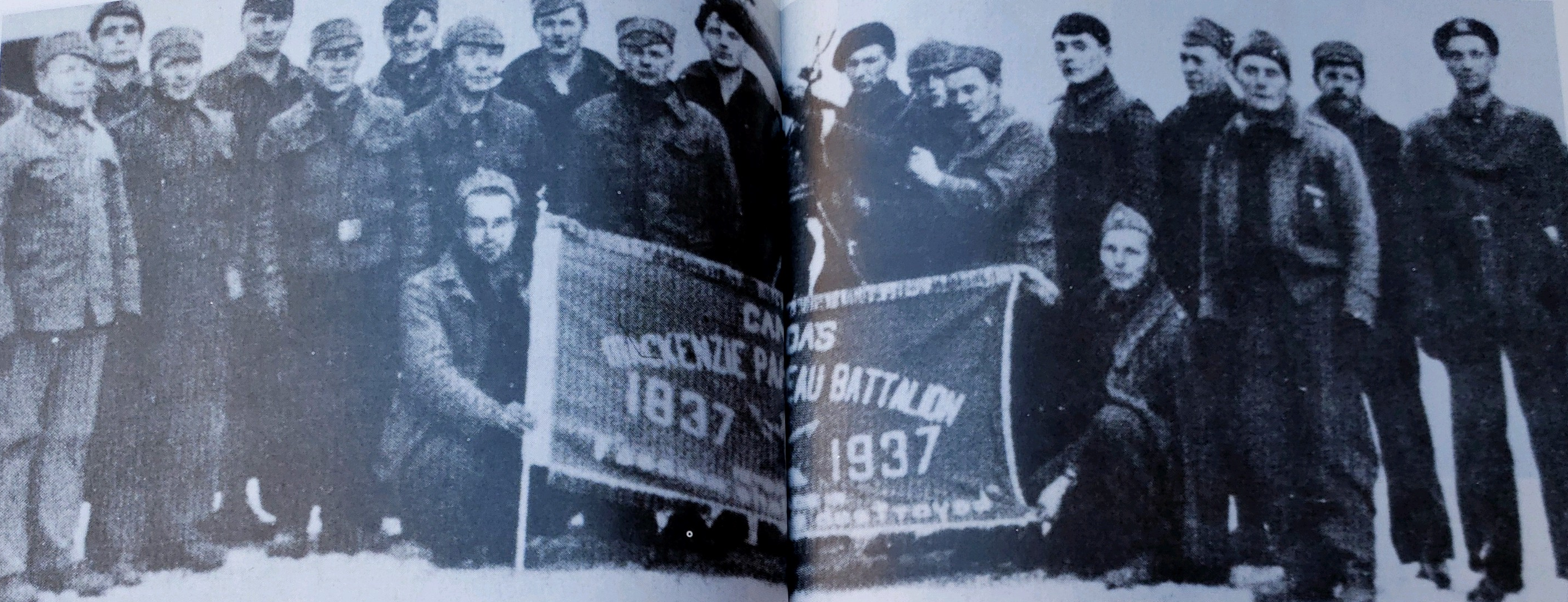

I first became acquainted with the members of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, the Brigadistas, about 30 years ago. At that time when I met them, there were just over a hundred left.

To me, the Spanish Civil War was a very important historical event marking those tumultuous years of the 1930s, years of economic depression so remarkably evoked in George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia. It was an event that inspired and incited film and art: Picasso’s painting of the destruction of Guernica; Frederic Rossif’s film, To Die at Madrid, and, even recently, Ken Loach’s remarkable film, Land and Freedom. It was about a struggle to contain fascism, a struggle that didn’t work, for, shortly afterwards, that struggle broke into a full-scale world war, in which Canada played her prominent part.

All I really knew at the time when I first met the Mac-Paps was that about 1,500 of them went to Spain to fight against fascism for the Republican cause, that they went to Spain to support a democratically elected government against a military coup and that the military was supported by the armed might in the thirties of Nazi Germany and Italy.

Less than half of those 1,500 returned to Canada a few years later. The rest were killed. And except for France, no other country gave as great a proportion of its population as volunteers in Spain than Canada.

I understand that, today, of that audacious and committed band, there are fewer than a dozen left. It is fitting that we recognize, 65 years later, the historic moment for which these men and women went to fight in a foreign war, a war which was not their own, a war in which Canada was not involved as a nation.

It is fitting also that a memorial to them be erected in this beautiful park in the nation’s capital. I would like to thank M. Beaudry and the National Capital Commission for their part in making this commemoration visible and lasting.Canadians do things for many reasons. We have a free society in which we give each other room to make decisions, to express ourselves, to have different political points of view. And the Mac-Paps decided that this cause was important enough for them to face the anger of their own government; to face the consternation of many of their fellow citizens at that time and for decades to come; and to face a life afterwards in which very few people would take the least interest in the kind of idealism that had sent them to Spain in the first place.

They were fighting for an ideal. They were fighting against fascism, which was like a rehearsal for the war to come. These men of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion of the XVth International Brigade of the Spanish Republican Army gave of themselves a passionate attachment to a civil war half a world away.

People of very diverse backgrounds supported these volunteers, people like Graham Spry, the founder and father of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. It was he who spearheaded the assessment as to what medical supplies and skills would be required in the war zone.

And shortly afterwards, a volunteer was dispatched from Canada by the name of Dr. Norman Bethune. Bethune was responding to an article written by Graham Spry, calling for the creation in Spain of a Canadian-sponsored hospital. This extraordinary and eccentric figure of great passion and medical genius, who came from Gravenhurst, Ontario, and was the son of a Presbyterian minister, was one of the first two volunteers in Spain. And it was there that he developed the dramatic innovation which helped to save hundreds of lives on those battlefields and thousands later in the war in Europe, the transportable blood transfusion unit.

About ten years ago, I was fortunate enough to spend some time with the American nurse who had helped Bethune with these transfusions. And her witness to history and to him stays with me. A year ago, I dedicated a statue to Norman Bethune in his birthplace, Gravenhurst. Recognition is now being paid to Bethune and to the others who went to fight for this cause.

As Victor Hoar and Mac Reynolds say in their colourful and poignant history of the war:

Men went to Spain to fight fascism, to defend democracy. A number certainly went to seek adventure. A few even to get away from their wives … A specific horror of fascism gave the volunteers the courage to venture abroad. It sustained them even after it was patently clear that the [other side] would win, and that they would lose.

Maurice Constant, who is here with us today and whom I met thirty-odd years ago, was a student at the University of Toronto, aged about 18, when he went to hear André Malraux speak about the Republican cause at Hart House in 1936. He was so moved that he asked Malraux what he could do to help. And Malraux said: “Go to Spain.” So he did. He was extremely young, but was one of the few Canadians to serve on the Brigade staff, becoming adjutant of the intelligence section at a very early age.

Like the other Mac-Paps, he fought in the battles of The Retreats, Teruel and The Ebro. Now, so many decades after these events, these Canadians are being remembered for their actions. But others have recognized them before us. The Spanish people and the Spanish government have remembered the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion. In 1996, the Spanish government invited the surviving members back to Spain, and honoured these Canadians with Spanish citizenship. To have played such a role in the development of another country is unique. For that alone, it is something that we should commemorate, because it is a part of our history as Canadians and as citizens of the world. And history, as Edmund Burke has said, is “a pact between the dead, the living and the yet unborn.”

Bethune, besides being a medical doctor and a genius, was also poet. And he wrote in his elegy, Red Moon, the following words:

Comrades who [fell] in angry loneliness, who [died] for us I will remember you.

Today, we are giving the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion a lasting memorial, here, where it should be, in their own land.

Thank you.