The Crisis in Spanish Government in the 1930’s

Spain inherited from the 19th century an autocratic monarchy, a privileged position for the Catholic Church, control of arable land by large landholders and a poorly educated populace.

Dealing with these problems was difficult enough, but reform would have to be carried out in the face of serious strains in Spanish society. There were powerful ethnic minorities that wanted, if not independence, at least greater autonomy, notably the Basques and the Catalonians. The relationship between capital and labour was marked by serious unrest and later would be met with government violence. The political scene was seriously fragmented: in the last election before Franco ended political expression in Spain, there were eleven parties in the Spanish Parliament (the Cortes).

Finally, reform would have to be carried out in the midst of a world depression in a country where half the population were poorly paid agricultural labourers and both land and capital were controlled by a small, highly conservative percentage of the population.

The Zamora Government – a Liberal Agenda: 1931

In 1931 the king agreed to democratic elections. The Spanish people, allowed to express their opinion at last, voted overwhelmingly for a republic and Alfonso XIII abdicated in April. The provisional government of the Second Republic was formed by Niceto Zamora, a liberal, who instituted a four point reform program: the separation of church and state including secular education, support for unions, limited autonomy for Catalonia and land reform.. However, progress in carrying out these reforms was slow, in part because Spain lacked the resources for his ambitious program. As reform foundered, Zamora lost his base of support.

The Swing to the Right: 1933

Elections were held in 1933 in which the Zamora government was defeated by the Catholic Party. The new government formed a right wing coalition that overturned all of the Socialist party reforms.

Education was returned to the church. The breakup of the large estates was halted, Catalonian self goverment was ended and, most seriously, union activity was suppressed by violence if necessary. The most extreme example of this was the revolt of the miners of Asturias who took over control of their state and declared a revolutionary soviet. The government sent in troops (commanded by Francisco Franco) and 5,000 miners were killed or wounded.

This action effectively ended the life of the Government and a general election was called in February 1936.

The last Republican Government: 1936

In January 1936, Manuel Azaña helped to establish a coalition of parties on the political left including the Socialist Party (PSOE), the Communist Party (PCE), the Esquerra Party and the Republican Union Party (but notably not the Anarchists who opposed the elections).

Right-wing groups in Spain formed the National Front which included the Catholic Party (CEDA) and the Carlists, a right wing paramilitary party. They were supported by the Falange Espagnola, the Spanish Fascist party.

Spain was now polarized into two camps: the left wing Popular Front and the right wing Nationalist Front

Nearly 70% of the more than 13 million eligible voters turned out for the general election in February. The National Front won 46% of the votes. The Popular Front won 47% of the votes and 55% of the seats, thus forming the new government.

The Popular Front government immediately began to enact a powerful reform agenda. They released left-wing political prisoners, introduced agrarian reform and granted Catalonia political autonomy. But the Spanish economy was weak, componded by depression and a flight of capital. These, along with Inflation and a weakening currency led inevitably to labour unrest.

17th July, 1936: Civil War

On the 17th of July, the military declared their opposition to the government. The leader of the miltiary uprising was General Francisco Franco. The Spanish Civil War had begun.

The Opposing Sides: Spanish Forces

In 1936 the Spanish Army was divided geographically into a Peninsular Army and the Army of Africa.

The Peninsular Army, the less well trained of the two, had 9,000 officers and 110,000 men. The government retained 85% of the men but only 50% of the officers. The remainder went over to the Nationalists.

The Army of Africa, based in Morocco, numbered 35,000. It remained under Nationalist control

The Civil Guard, in theory a police force, had 70,000 men and officers. Over 40,000 joined the Nationalists.

The Assault Guard, another police force, had 30,000 men and went over to the Nationalist cause.

Each side therefore retained about half of the men under arms but the officer corps went overwhelmingly over to the Nationalists.

The Opposing Sides: International Support

This uneven division of the Spanish forces was also to be reflected in international support.

Both Germany and Italy actively supported the Nationalists during the war, Germany with 10,000 troops and Italy with 60,000. Both countries supplied arms and materiel as well as troops. The Germans also provided air cover.

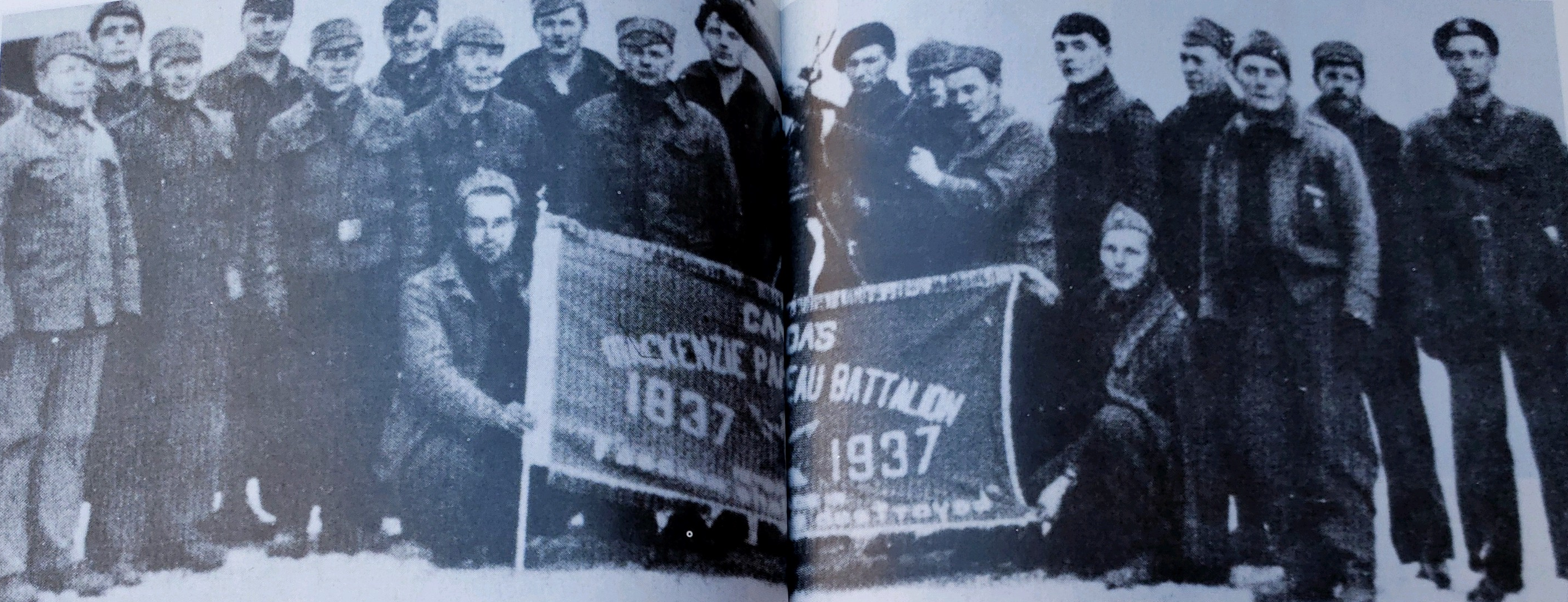

The Soviet Union supported the Loyalists, also with arms and materiel and, importantly, aircraft, but couldn ‘t match the quality or quantity of the fascist powers. The government attempted to obtain other support but the League of Nations ended by imposing an arms embargo (which Germany and Italy ignored). The government was able however to obtain international support in the form of volunteers. 40,000 volunteers travelled to Spain to fight in the in the International Brigades (although there were never more than 15,000 to 20,000 in the field at any time). Highly motivated, they unfortunately suffered from the poor quality of their arms, mostly First World War issue.

The Battle Lines

The main battle lines reflected the division of the armies. The government retained control of the eastern and southern part of Spain, but as the Army of Africa was airlifted to the south of Spain (using German aircraft) Franco was able to rapidly increase his control in that part of the country.The main battle lines had thus been drawn and the resources of men, leadership and arms very unequally divided—they would continue to tilt slowly but inexhorably toward the fascists throughout the war.