Brunete: July 1937

The Western approaches to Madrid pass through a broad valley 60 to 80 kilometers long and 15 to 25 kilometers wide. There are a number of towns of which Brunete is the largest, giving its name to the major battle that surged back and forth across the plain for 20 days in July 1937.

Since the previous November Franco’s forces had occupied the towns on the plain and the Heights of Romanillos that flanked it. The government planned a major offensive against these forces mobilizing 10 divisions one of which held the XIIIth and the XVth International Brigades.

On July 6 with 8 Republican divisions moved into position on the hills overlooking the valley and descended onto the plain where they met heavy fascist resistance. The XVth International Brigade composed of the Abraham Lincoln, the George Washington, the Dimitroff and the British Battalions was given the task of taking the village of Villanueva de la Canada (a curious coincidence for the 70 odd Canadians who participated, mostly in the Lincolns). They took the town after two days of heavy fighting.

From Villanueva de la Canada, the Internationals advanced toward the Fascist positions on the Heights of Romanillos at a place called Mosquito Hill. The Republicans had made a rapid advance across the plain but at the foot of the Heights the advance stalled. With the Battalions on the low ground and the Fascists dug in on the Heights attack after attack up the slopes failed. On the 13th of July the attacks were abandoned and the two International Brigades were ordered into support for Spanish republican units. After another three days of heavy fighting they were sent to the rear to recover.

Their respite didn’t last long. On July 16th, the Fascists mounted a major counter-offensive with 20,000 men, 100 tanks and 100 aircraft. The Internationals were ordered back into battle as Franco’s forces swarmed down onto the plain forcing back the Republicans in a bitter action that lasted 8 days.

For a week the two forces fought desperately across the Brunete valley, battalions colliding and bouncing off one another to hurtle into another deadly engagement somewhere down the line – where there was a line. More often than not the fights were conducted on the run as the combatants clawed their way up and down the barancas. Gradually, the southern part of the Republican sector began to crumble. Brunete itself was captured after barrages of artillery shells literally smashed the town to pieces.

On the 26th of July the Republicans withdrew their forces. The four Battalions of in the XVth Brigade had taken heavy losses. The Lincolns’ commander was killed. The losses of the Lincolns and Washingtons was so great that the two Battalions were merged into the Lincolns on July 16 and the Washingtons (as it turned out) were never reformed. Of the 70 or so Canadians in the battle, one-third were killed and two successive leaders of the Canadian section in the Lincolns fell in a three day period. A fourth leader would be needed before the battle was ended.

While the Republicans had demonstrated their ability to deploy and maneuver at Army Corps level, the were simply unable to match Franco’s strength. They threw all of their forces into the battle on July 6 with virtually no reserve while Franco was able to maintain a steady supply of fresh troops and armour and, in the middle of the battle, to stage a major counter-offensive. The uneven distribution of men and materiel and the effectiveness of German and Italian support to Franco had shown to disastrous effect.

The ‘Macpaps’

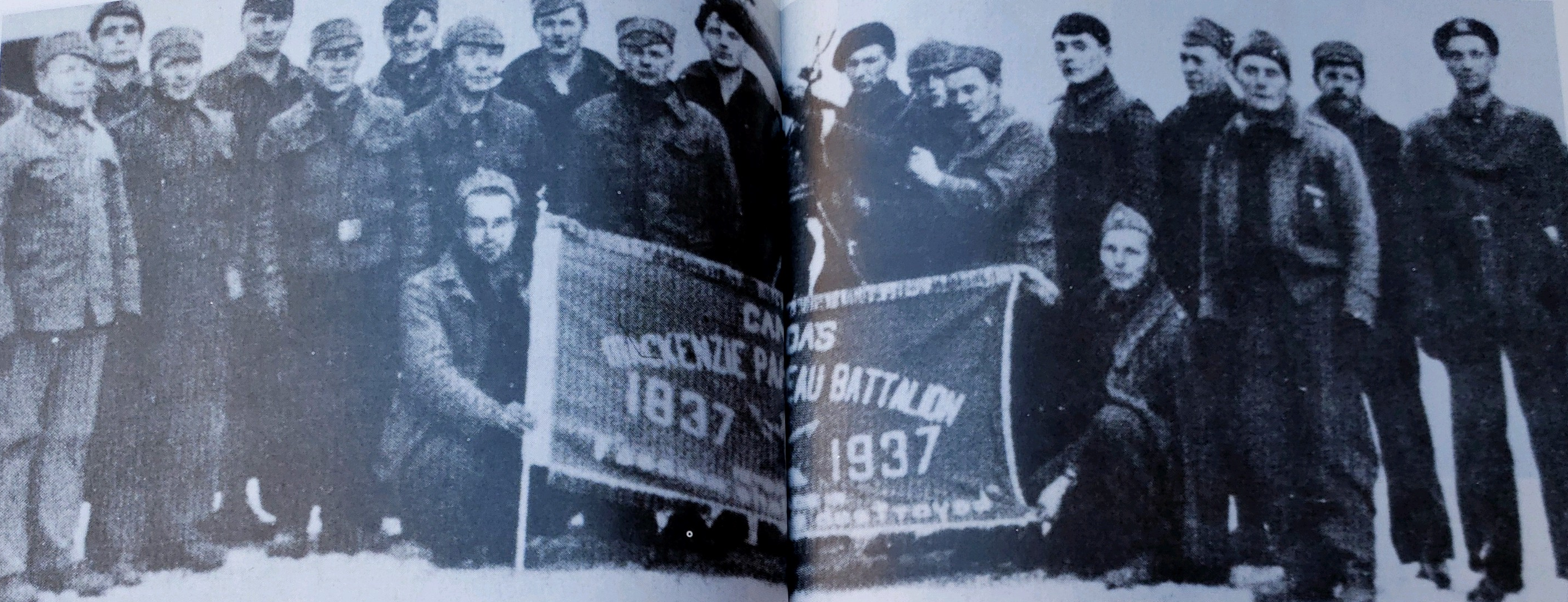

In April 1937 a number of Canadians got together to discuss the possible formation of a Canadian Battalion within the XVth International Brigade. The name they proposed was the Mackenzie-Papineau, after the English and French leaders of the 1837 rebellions against undemocratic British colonial rule in Upper and Lower Canada. (It surely didn’t hurt that 1937 was the centenary of the rebellions.) Throughout the spring volunteers were regularly arriving at Albacete and a new battalion was in fact formed but the Americans wanted it to be named as a third American Battalion (in addition to the Washingtons and the Lincolns). Their hope was that with three battalions in the field, they could form an American brigade. As compensation to the Canadians, who would not then see their own brigade, they offered to provide an all Canadian company within the newly formed Battalion.

The Canadians mustered a number of arguments in support of their own battalion. There were now (the Spring of 1937) over 500 Canadians in the field, about half as many volunteers as the US although Canada then, as now, had only about one tenth the population. There was also the argument that a Canadian Battalion would help to publicize the war back home and aid in raising further support.

In the meantime, the newly formed and still unnamed battalion remained continued to train and continued to be unnamed for reasons no longer known. For whatever reason, the delay allowed the Canadian representations to the International Brigade Command to proceed and Canadian proposal was adopted by the Brigade command.

A.A. MacLeod who had travelled to Spain to arrange for the return of Norman Bethune subsequently travelled to Tarazona in June to address the massed Canadians and Americans of the new battalion. He spoke movingly for two hours citing the founding of Canada, the war of 1812, the rebellions of 1837 and the present situation in the world. Those who heard him were roused by the speech and when asked if they would endorse the new battalion name, did so unanimously, including the Americans who were not unhappy about the new battalion – they thought the Canadians deserved it.

The new Battalion was not entirely Canadian at that point – in fact Americans outnumbered the Canadians in the Battalion by two to one. As new recruits continued to arrive in Albacete from Canada however they were usually assigned to the Macpap Battalion. Even so, Canadians typically accounted for about half of the members of the Battalion. Many Canadians ended up in other Battalions – some in Slav Battalions where, because of limited English language skills, they felt more comfortable or in artillary batteries, transport units or medical units. Many had been killed or wounded in the Canadian Section of the Lincolns before the Macpaps were formed and many continued in the Lincolns. Nonetheless, the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion was to become the symbol of Canadian participation in Spain and remains so today.